By Dimitris Grammatikoyiannis

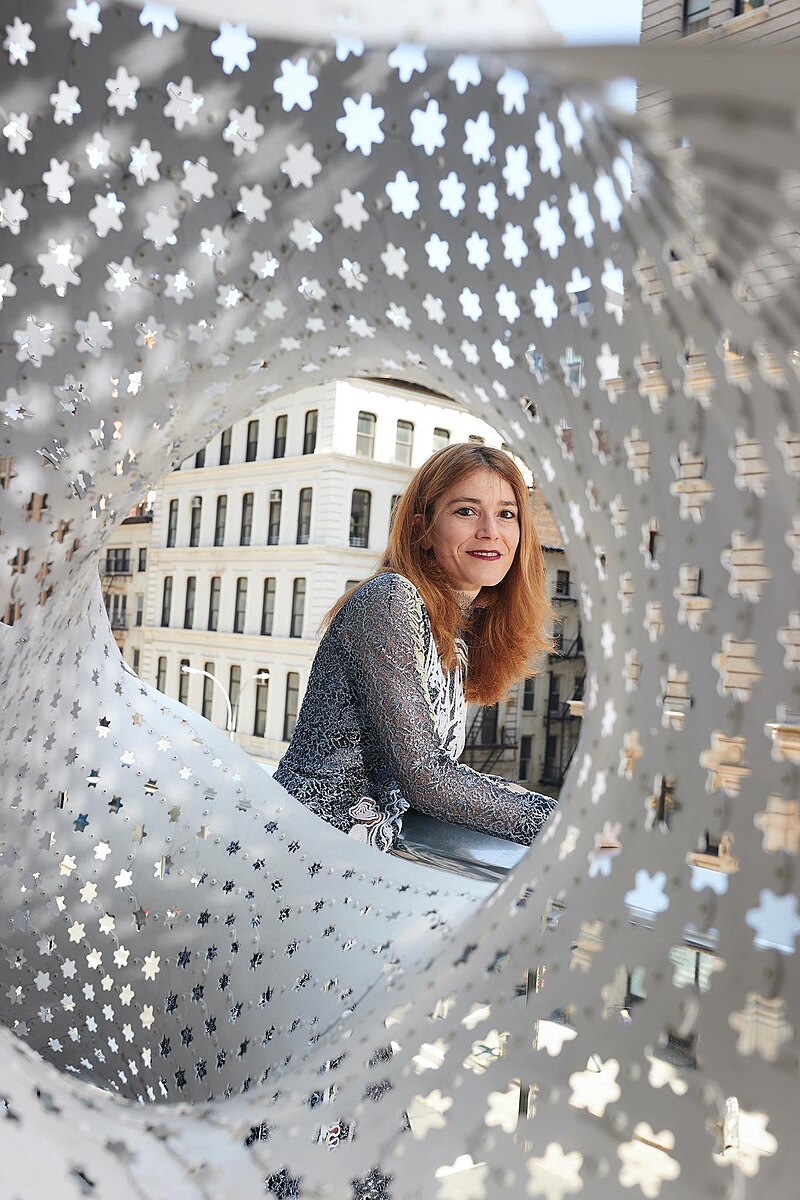

Dr. Sozita Goudouna is a dynamic and interdisciplinary figure whose work spans the realms of curation, academia, and artistic advocacy. Born in Athens, Greece, she moved to London in 1996, where her academic pursuits took root in philosophy, theatre, and literature. With a deep intellectual foundation in high modernist theory, her academic journey set the stage for her innovative approach to the intersection of the visual and performing arts.

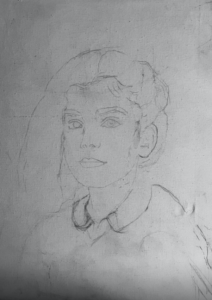

(Sozita’s portrait, drawn by her mother Polyxeni Tsakiri )

(Sozita’s portrait, drawn by her mother Polyxeni Tsakiri )

In this exclusive interview, she shares her career highlights, challenges and thought processes from her groundbreaking book Beckett’s Breath: Anti-theatricality and the Visual Arts (2018), published by Edinburgh University Press, to founding the nonprofit organization Greece in the USA, which aims to showcase Greek artists on the global stage.

Her pioneering career and curatorial vision extend far beyond the conventional, embracing the role of art as a means of social dialogue and cultural exchange. Whether organizing art residencies, creating platforms for dialogue, or pushing boundaries through experimental curation, Sozita Goudouna continues to shape the future of contemporary art and cultural exchange, proving herself as a formidable force in the global artistic community.

A true innovator and hometown hero, I deeply admire her brilliance, tenacity, and unwavering belief in the inseparable connection between art and fashion. From the complexities behind the designs of Dior to the U.S. incarceration system, Sozita Goudouna exemplifies profound thought and insight, embodying the spirit of many great Greek thinkers before her. She is relentless in harnessing the transformative power of art to educate, inspire, and motivate people worldwide.

As a fashion editor and stylist based in Athens, I have long been an admirer of Sozita Goudouna. She not only blurs boundaries but is also a constant source of inspiration that serves as a powerful reminder to push creativity beyond the obvious, embracing both Greek and global realities that affect not just me but all of us. It often feels like we’re living in a time where there is more light and darkness than ever before. This contrast can be hard to navigate, and her clarity offers a fresh perspective for art and living in general.

Dimitris: Sozita is a unique name, is there a story behind it?

Sozita: My mother gave birth to me quite late for that period (over 40 years old) and had experienced many abortions and miscarriages before I was born. At the same time, my father’s mother, who passed away when he was seven years old, was named Soteria, which means “savior” in Greek. My very creative mother had a beloved nephew, my cousin Sozos Tsakiris. Thus, she thought that I would be the feminine version of Sozos and coined the name Sozita, which doesn’t really exist. I was also saved as an eight-month-old baby who came down the birth canal with my feet! Perhaps I was in a hurry to save!

Dimitris: Your work generally has been characterised by your interest in supporting and promoting Greek artists. What are the obstacles you have faced so far regarding this venture to internationalize Greek Art?

Sozita: When discussing the challenges of Greek cultural diplomacy, we usually focus on limited budgets and resources, which can hinder the organization of cultural events, exchanges, and programs, impacting their reach and effectiveness. The lack of resources and public and private funding typically frames the problem of internationalizing contemporary Greek art. However, negative stereotypes or misconceptions about a culture can create similar barriers to engagement and acceptance, making it difficult to foster genuine interest and connections with other cultures, such as the American.

Insufficient knowledge about the importance of cultural diplomacy among policymakers and the general public can lead to a lack of support for groundbreaking cultural initiatives, resulting in a repetition of safe formulas that may seem successful due to audience participation but are often inconsequential in their impact on innovative cultural production.

I was perhaps born or raised with a Don Quixote-like approach to life and culture, and I tend to overlook obstacles, as this is the only way to continue producing and presenting art, especially in live arts, while also engaging in scholarly research in the humanities. By overlooking these obstacles, I have come to appreciate the invaluable altruistic support from contributors, artists, friends, and the broader audience. I have experienced this generosity over the last three years since establishing The Opening Gallery and Opening Art Initiative in Tribeca, New York. According to the wider public, a different cultural ecosphere has been established at The Opening, beyond the traditional art market.

The nonprofit cultural venue and initiative supports a heteroclite art ecosystem and project space that attempts to go beyond prevalent gallery models in Tribeca. The Opening Gallery has collaborated with The Watermill Center, Columbia University, Maison Francaise NYU and has hosted the New York Arab Festival and events organized by MoMA curators while it collaborates with Sorbonne Art Gallery in Paris. The Gallery has presented international and US based artists including Andres Serrano, Sagarika Sundaram, Michele Zalopany, Christopher Knowles with Sylvia Netzer, “The Order of the Third Bird,” Brian Block, Kenneth Goldsmith, John Zorn, ORLAN, The Shoplifter, Luciano Chessa, Daniel Firman, Hans Weigand, Raúl Cordero, Jessica Mitrani, United Nations artist-observer Yann Toma, Warren Neidich, Coleman Collins, Constance DeJong, Charles Gaines, Jimmie Durham, Leslie Hewitt, Jimmy Raskin, Agnieszka Kurant, Olu Oguibe, Martha Rosler, Allen Ruppersberg, Chrysanne Stathacos, Leah Singer, Ronan Day-Lewis, Orit Ben Shitrit, Mahyad Tousi, Regina Scully, and Bill Hayward among other artists.

Dimitris: You are the author of Beckett’s Breath: Anti-theatricality and the Visual Arts. What were the motivations for writing this book and what did you try to investigate in the era of climate crisis that respiration becomes valuable and dangerous at the same time, due to microfibers?

Sozita: The current “shortness of breath,” derived from atmospheric politics, pollution, health concerns, political pressure, and social injustice, makes the book particularly relevant. Artists frequently engage with themes related to climate change, environmental degradation, and sustainability, raising awareness about

ecological crises, with breath being central to this discussion. My initial aim was to explore respiration in its connection with poetics, visual culture, live arts, the environment, and embodied politics. I was humbled when Prof. William Hutchings remarked that my book “surely is the most ever said about the least in the entire history of literary criticism” and Prof. Rustom Bharucha stated that “Dr. Goudouna’s book is outstanding – with no exaggeration, it is unique, not just in terms of its contribution to Beckett Studies, but in the larger field of interdisciplinary research.” Prof. Simon Critchley also commented that “Ms. Sozita Goudouna’s book left me breathless.” The book examines breath in the context of performing and visual arts from the 20th century to the present, situating the work within its historical and social context. It introduces a range of key theoretical perspectives that can be used to analyze this primary

human physiological function and its relation to arts and culture. The focus on breath is highly pertinent to the studies of human performance and the nature of embodiment in relation to cultural expression while expanding the medical humanities. The book attends to fifty breath-related artworks (including sculpture, painting, new media, sound art, and performance art) while focusing on the late sixties and early seventies, showing how Conceptual Art and a generation of conceptual artists, fresh from sixties political dissent and communal purpose, dismissed the art object as a mere pawn in the art market.

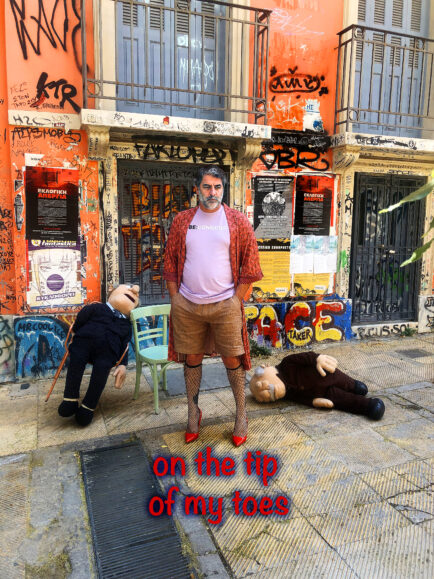

Dimitris: How is your curatorial practice influenced by fashion?

Sozita: In an era of continuous experimentation with fashion, the relationship between art and fashion is vital, perhaps more than ever. One of the most interesting projects I was involved in, which included a strong element of fashion, was the Dior x David Zwirner Gallery collaboration in 2019, before the pandemic. As studio director at Raymond Pettibon Studio, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Kim Jones on the Pettibon collection. According to Jones, “the inspiration [for the collection] came from the artworks of Raymond Pettibon, particularly from the more romantic aspects of his work, tying that into the loves of Monsieur Dior, which were nature and the romance of the House.” The collection included items featuring works handpicked by the designer, as well as original prints. David Zwirner Gallery, signaling its first outpost in continental Europe, featured a solo exhibition by Pettibon and pieces that inspired Kim Jones for his fall men’s collection for Dior.

I will never forget my collaboration when I first started to work in New York at the Performa Biennial 2015, where Performa managed to unite the worlds of art and fashion at St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue during the opening night of Performa 15. A collaboration between visual artist Francesco Vezzoli and David Hallberg, one of our most celebrated ballet dancers, “Fortuna Desperata” was a one-night-only performance that explored the earliest origins of ballet. Designed by Fabio Zambernardi for Prada, Hallberg’s costume was a fanciful doublet, adorned with metal embellishments, mismatched stockings, and a bow in the back.

Dimitris: We have a legacy from the twentieth century: expressionism, surrealism, pop art, abstract art, etc.

Do we live in a postmodern era, or are we beyond that?

Sozita: Indeed, modernism and late modernism fostered movements like expressionism, surrealism, pop art, and abstract art. Postmodernism shifted many grand narratives surrounding art and critical theory, expressed in architecture and the arts from the late 70s, especially in the States. We may now be beyond this movement, with many theorists attempting to coin new terms like “alter-modernity” (Bourriaud), but these terms have faded away. It is important to continue using concepts like postmodernism even if they do not fully encompass our current cultural experience. Nevertheless, as Bruno Latour has argued, “we have always been modern,” and Robert Rauschenberg stated that “all art was once contemporary.” Therefore, moving beyond distinctions might be helpful, but only if we remain aware of the meaning of each term.

Dimitris: How important is it for you, through art to make a statement for social issues?

Sozita: The commitment to social change and the desire to provoke thought and dialogue about pressing political issues should be of primary concern for the arts. Socially engaged art addresses history, past injustices, collective memory, and the ongoing impact of historical events on current society. Many artists focus on issues such as racial equality, gender rights, and LGBTQ+ rights, highlighting struggles against discrimination and advocating for equity. Artists explore themes of identity and belonging, the socio-political factors driving displacement and address the consequences of war, militarization, and violence, often portraying the human cost of conflict and promoting peace. At the same time, art practices critique capitalism’s impact on society, political power structures, corruption, and the influence of money in politics, often using satire or direct commentary. With the rise of technology and data collection, many artists examine issues of surveillance, civil liberties, and the impact of digital culture on personal freedom.

In this context, the first exhibitions I curated on behalf of the non-profit “Greece in USA,” I founded in 2020 for the promotion of contemporary Greek art in New York, addressed the criminal justice system, prisons, and incarceration. During the global pandemic, amid restrictions and limitations, I invited Greek artists to reflect on the US incarceration system, and the exhibition “The Right to Silence?” opened at CUNY (City University of New York). The title references the Miranda rights, the right detainees have to remain silent during initial police interrogation. In a poetic rather than accusatory tone, the exhibition attempted to address US issues regarding the criminal justice system, racial discrimination, private prisons, and the limits of freedom in general, more at https://greeceinusa.com/project/the-right-to-silence/ & https://greeceinusa.com/project/the-right-to-breathe/

Dimitris: Can you tell me about THE PLEASING EFFECT at the Fairytale Castle in Argilis Messinia?

Sozita: The Pleasing Effect is an annual marathon of live and visual acts and a collaboration with COMOTIRIO, the artist-run initiative and co-working scheme of visual artists Naira Stergiou & Eriphyli Veneri. The project is one of the most enjoyable projects I have worked with, since the collaboration and dialogue were so unique, spontaneous, and straightforward, thus, we aim to organize it every year!

The project draws from diasporic utopias and the Castle of Fairy Tales. In the 1960s, Harry or Babis Fournier, born Charalambos Fournarakis originally from the city of Filiatra, a Greek doctor from America, returns to his birthplace and builds his own unique reality to generously share with all of us- the ‘Castle of Fairy Tales’ – a castle state, a country within a country, another Narnia, the “Disneyland of our place.” He builds this state in detail, a city within his city, based on childhood memories and the timelessness of imagination. In order to relieve, as stated in the inscription that welcomes the space, the romantic era in this place. And indeed, ignoring any ‘objective’ judgment of beauty, Dr. Fournier romantically defends spontaneity as a source of creation, as a perceptual reception, as a decoding of the world.

Dimitris: What are the differences in the way of thinking between the Greeks in Greece and the Greek diaspora?

Sozita: For many in the diaspora, maintaining a Greek identity can be a conscious effort, leading to a strong sense of community and cultural pride. In Greece, individuals may take their cultural identity for granted, as it is more deeply integrated into their everyday lives. At the same time, Greeks in Greece may have a collective memory shaped by historical events unique to Greece, such as the Greek War of Independence or economic crises. The diaspora often has a different historical narrative, influenced by migration experiences, adaptation challenges, and the pursuit of opportunities abroad.

“Greece in USA” investigates these discrepancies and in this context, we presented Nitouche Anthoussi’s “Species of Heterotopias,” a project that addressed these issues. The artist investigated the notion of “Utopia,” and its historical and philosophical references, with her core focus being on socially surveilled realms such as Ellis and Leros islands thinking about Greeks that lived a life of confinement either at Ellis or Leros islands. By comparing “carcerality” and imposed social or political confinement between the two faraway islands – that are separated by the Mediterranean and the Atlantic – the project included interviews, archival material, photographs, and 3D scanning of the premises and the buildings that are inaccessible to the public.

I need to thank Hayley Hill for her invaluable help with this interview and layout.

(Chromocommons group exhibition with Shoplifter/Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir, The Callas and Calassetes, Misha Milovanovich, Leah Singer and Tula Plumi, The Opening Gallery, 42 Walker st, Tribeca, June, 2023.)

(Chromocommons group exhibition with Shoplifter/Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir, The Callas and Calassetes, Misha Milovanovich, Leah Singer and Tula Plumi, The Opening Gallery, 42 Walker st, Tribeca, June, 2023.) (The British School at Athens, in partnership with the British Council, Edinburgh University Press and Nissos Academic Publishing, hosted the Greek book launch of Dr. Sozita Goudouna’s book “Beckett’s Breath,” May 9th 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYg5cfaF3SI&t=12s)

(The British School at Athens, in partnership with the British Council, Edinburgh University Press and Nissos Academic Publishing, hosted the Greek book launch of Dr. Sozita Goudouna’s book “Beckett’s Breath,” May 9th 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYg5cfaF3SI&t=12s) (Francesco Vezzoli and David Hallberg, Fortuna Desperata, Performa Biennale 2015, St. Bartholomew’s Photo by Brad Barket)

(Francesco Vezzoli and David Hallberg, Fortuna Desperata, Performa Biennale 2015, St. Bartholomew’s Photo by Brad Barket)

(THE PLEASING EFFECT curated by Sozita Goudouna featuring COMOTIRIO, produced by Out of the Box Intermedia and Greece in USA, July 12, at the Fairytale Castle of Filiatra in Agrilis, Messinia, Greece.)

(THE PLEASING EFFECT curated by Sozita Goudouna featuring COMOTIRIO, produced by Out of the Box Intermedia and Greece in USA, July 12, at the Fairytale Castle of Filiatra in Agrilis, Messinia, Greece.)